Climb to Summit of Mt. Everest via North Ridge Route

From the book, Seven Summits, published by Mitchell Beazley, 2000

A description by Jeff Shea of his summit of Mount Everest, 8850 meters (29,028 feet) of elevation, via the North Ridge route in Tibet. He did not use supplemental oxygen except from Camp 3 at 8200 meters (26,896 feet) and above.

jeff shea

the spirit of tibet

(begins on page 52 of the book Seven Summits)

Foreward from Book Seven Summits by Steve Bell, Editor

“Though the Tibetan side of Everest is regarded as a tougher climb than the Nepalese side, many climbers still prefer Tibet. Barren and windswept, with the striking pyramid of Everest visible for many miles, Tibet makes a lasting impression. In spring 1995, climbers enjoyed unprecedented good weather on the Tibetan side. By the time the monsoon spilled over the mountain from Nepal, 67 climbers had succeeded on the North Ridge. But Everest was no pushover, as Jeff Shea explains.”

The story by Jeff Shea… The Spirit of Tibet

After sailing across the ocean and traveling many miles by land, I reached the ridge above Namche Bazaar in Nepal and spied the windblown cap of Mount Everest for the first time in my life. During the weeks that followed, I had vague aspirations about climbing the mountain, but they seemed like pipe dreams. My first grapplings with Himalayan altitude, as I panted up a 6000m peak a few weeks later, emphasized Everest’s unattainableness. The Himalayan magnificence was upon me, more impressive than I could have imagined, the sheer size dwarfing any other mountain range in the world many times over.

On that journey in 1983, I stood at Kala Patar and surveyed the grand vista of icy peaks; I huddled in the warm emptiness of a mess tent at the South Col Base Camp at 5200m, in awe of those men and women who were actually on an Everest expedition; I breathed in the Tibetan culture at Thyangboche Monastery during the Mani Rimdu festival, delighted, marveling over the color and richness of the costumes of the masked dancers. As a child might view it, it was all new and exciting.

Unable to sleep and lured by the moonlight, I stepped into crisp December night, scrambling above the rooftops of Thyangboche. In the vast canyon formed by Ama Dablam and the Everest massif, the perfect silence was suddenly broken by the echoing trumpet of the monastery’s ancient horns, dispelling evil spirits and resounding with the purity of good intent. Magic! I came away from my first Himalayan trip knowing why the local animists attributed god-like powers to the mountains. Indeed, they seemed to have a spirit of their own.

Twelve years later, I found myself lured again by the Himalayas. Except this time I went to the North Side of Everest, and this time I was not a trekker, but a climber. On the journey from Lhasa – at the top of the astonishing monastic ruins of Xegar – Cho Oyu, Shisha Pangma, and Makalu appeared amid the clouds. While there, a Xegarian monk portended, “You see Everest, good luck. You no see Everest, no good luck.” Just as we gathered to leave, the clouds cleared to reveal Everest in its all glory, towering over the rest of the landscape.

Jumping off the back of the gear truck, dusted from head to toe, and nauseous from the drive to 5200m, I set up my tent, where it would remain for two months. It was 12 April 1995. At Base Camp, I wrote:

“Last night was the worst night I’ve had. I was dehydrated and was still adjusting to the altitude here. At times like that, the mental battle is worse than the physical one. To resist thoughts of despair takes a strong will, and yet to discern when it is advisable to abandon a project take good judgment. I do not feel it is, on one hand, necessary to make the summit of this mountain, but still, to abandon it now would render all the effort I took to get here a folly. I have risked an awful lot to climb this mountain…. The greatest part of this journey is not the climb but all the other combined sights and sounds. The people here are a rather amazing collection of accomplished individuals. Some are great mountaineers. Some are adventurers and photographers, others doctors, or women attempting firsts in the climbing world.”

The Base Camp affords a sweeping panorama of Changtse, the North Ridge, the Great Couloir, the North Face, and the summit pyramid, with the jet stream sailing off in a vaporous plume. The route winds move clockwise around Changtse, through the ice pinnacles of the East Rongbuk Glacier. Twenty-one kilometers of trail ends at Advanced Base Camp (ABC) in full view of the North Col and the summit pyramid.

Resisting the trend to rush headlong to ABC, I followed the advice of Australian Jon Muir, who reckoned the best way to acclimatize was to simply take it easy and hang out at Base Camp. For 12 days I did so.

I arrived at ABC on 25 April. Two days later, I traversed the glacier to the foot of the precipitous slope leading to the North Col, a picturesque mass of tumbling house-size blocks of ice that must be negotiated to reach the Col itself. Light avalanches rumbled off to my left from the flanks of the North East Ridge. A seldom-discussed Everest disaster occurred in June 1922, on the second-ever expedition to the mountain, when the slope I was about to climb avalanched, taking the lives of seven porters. In all, avalanches from the slopes below the North Col have killed at least 16 people, nearly as many as the far more notorious Khumbu Icefall.

My acclimatization schedule sent me to the Col four times. Although in some places it was steep enough to make an unroped fall fatal, the snow was soft and felt secure. Wending my way around the blocks of ice brought me to the Col at 7050m, affording a clear view of the North Face, its enormous Great Couloir ending in an ice cliff of unimaginable dimensions. The summit seemed as if you could reach out and touch it. The tents were nestled on the leeward side of an ice buttress, sheltered from the 70 knot winds that scoured the North Face.

On 30 April, I climbed at Camp 2 at 7600m. From the North Col, the route continues on a wide, gradually steepening saddle of snow. At first, I was comfortable as the sun was out and the wind was just a breeze. Almost imperceptibly, the conditions deteriorated. Visibility shrank to a few meters and the chill crept through my heavily insulated boots. The dwindling of my inner core’s heat became a concern. I had been using the fixed ropes to safeguard a fall, only to discover that the top snow stake holding them slide easily out of the ice. At the top of the snow saddle, I arrived at a pair of tents flapping violently in the wind.

My partner Fred Zalokar and I feebly made unappetizing soup, and then scooped our spilled water from the tent floor. I slept restlessly, constantly aware that the wind was blowing like crazy. I wondered what might happen if the tent ripped apart. The next morning, Fred and I took seemingly forever to get ready to descend. Thoughts of putting our boots on occasionally roused us from our altitude-induced stupor long enough for us to look up from our sleeping bags, then we would slide back into a senseless haze. It took me 11 days at lower altitudes to recover from my visit to 7500m, most of it spent at Base Camp. I wrote:

“I have been like a zombie since I returned from up above. I have been bothered by dry throat, lethargy, shortness of breath, stomach aches, diarrhea, and feelings of claustrophobia since I arrived back here at Base Camp. My lower lip is a blistered mess. I must have forgotten one morning (just one!) to properly protect it, and now it is a maze of blood, blisters, and puffiness. Also, I have been coughing since I have been here. It is like trying to scratch an itch that I cannot reach.

We sit down here at Base Camp day after day watching the weather change. In the morning it might be clear, and by afternoon, snowing. The weather above all scares me when it comes to this mountain. If I am going to make a summit attempt, I will only do so, as I now see it, when the skies are clear and calm for as far as you can see. I figure this is the only day that has any chance of being ‘reasonably safe’ to climb Mount Everest.”

On 12 May, I was back at Camp 2. I felt stronger, the minor miracle of one month’s acclimatization. Above Camp 2, the route ascends through a patchwork of rock and packed snow. I climbed alone enjoying the sunny, windy solitude. When I reached 8000m above a 30 degree snowfield, I considered my acclimatization completed. It was time to descend and shore up my strength for a summit attempt. I spent a solid week eating at ABC to regain some of the 14kg lost from my 82kg frame.

One evening during my respite at ABC, a buoyant Alison Hargreaves dropped into our mess tent for a visit – she appeared as fresh as she did on the flight to Lhasa at the beginning of the expedition, when I absurdly mistook her for a non-climbing companion of another climber! She had just successfully completed an unassisted climb without oxygen. Her goal was to climb the three highest mountains in the world in one year. Three months later she was dead, having been caught in a storm on her way down from the summit of K2.

On 20 May I was back at the Col with Yves Detry, Patrick Hache, and Andre Tremouliere. The next morning, radio reports informed us that two climbers were blocked by high winds for the third day in a row at Camp 3. Given it was late in the season, I concluded wrongly that this year’s unusually good weather was at an end.

The next morning, I laced up my crampons and grabbed my ice axe, preparing to descend. Yves, a constant source of good cheer, inquired where I was going. When he reminded me of their special stockpile of French cheese, sausage, and crackers, my resolve to abandon camp vanished. As if to validate my gastronomical instincts – and Yves’ experienced advice – the winds died down during the night, allowing us to move up the saddle the next morning. Arriving at Camp 2, my French companions declared that the wind, having brewed up again, was advising us against continuing. I “leaned into it” and moved up a few hundred meters to camp with Lakpa Gelu and Lama Dorje of Nepal.

The following morning, in fine weather, Lakpa, Lama, and I first passed the 8000m snowfield, then climbed a snow gully to arrive at Camp 3 by early afternoon. The sloping high camp lay at the rocky base of the so-called Yellow Band, a place where finding protection for the wind was extremely difficult. It is rumored that in 1952, when the North Side was off-limits to Westerners, six accomplished Russian climbers were literally blown off the face of the mountain from the Camp 3 area.

We took a meal in the late afternoon and bedded down while the sun was still shining. After six weeks of restless nights, I now used supplemental oxygen for the first time. My frigid fingers and toes felt a sudden rush of warmth, and I slipped away to dream-filled and euphoric slumber.

At 10 p.m., I awoke, my lungs pulling vainly for air on an empty bottle. We drank tea and checked our gear, departing just after midnight. It was pitch black. Our vision was confined to the narrow beams of our headlamps. We moved straight up through the snow and rock gullies, seemingly for hours. I longed for an end to the incessant upward effort. We then began traversing down and to the right, signaling that we had arrived at the North East Ridge itself. The air was remarkably still. Horizontally traversing an exposed patch of snow to a fixed line, we jumared up and around the First Step. Approaching the fabled Second Step, we ascended sloping terraces of crampon-scratched shale only a boot wide. I used my axe like a walking stick to balance on my crampon points. Perhaps fortunately, the moonless darkness rendered the drop-off invisible. Seventy-one years earlier, in 1924, Mallory and Irving were last seen alive in this area. The shelves of shale supported old loose ropes, dubiously secured by pitons, in some cases no more than flat, rusting iron anchors placed into cracks of eroding, stratified rock. The ropes’ false security was worrying. However, a week later another climber, while coughing up bowlfuls of lung matter on descent, was held by them when he slipped.

At about 4 a.m. we scrambled up rocks to the foot of the Second Step, a high, ungainly outcrop of rock at 8600m. Visible from Base Camp, this was the crux of the North Ridge Route. In 1975, the Chinese left a relic of their epic ascent: the “Chinese Ladder.” Lakpa stepped onto it and climbed to the top rung. Then, wrapping his forearm around a half dozen fraying ropes that dangled from above, he hoisted himself up and out of view. As I came over the edge of the Second Step, I was transfixed by the awesome view. The North East Ridge was bathed in the golden light of dawn and the summit pyramid looked remarkably close.

After passing the Third Step, the final rock obstacle on the ridge, the route came within one meter of the East Face. I could not resist leaning over it to check it out. Space catapulted, near-vertically, thousands of meters to a valley that spread out eastwards towards Kanchenjunga.

At 8750m, a final snowfield separated us from a platform from where, I had been told, the summit was an “easy walk.” Near its top, Lama disappeared to the right among some rocks. I followed Lakpa up to the left, remaining on the snow unroped. My ice axe flew back at me, having hit solid ice just under the surface. I glanced back and was a bit shaken by the meaning of the commitment I had made. If I fell, could I self-arrest? More likely I would hurtle uncontrollably down the North Face. It being an exceptionally fine day and only about 8 a.m., I afforded myself the luxury of chopping steps for security. After laboring for half an hour, I came to a frayed remnant of rope. Lakpa peered over the platform and motioned to me that it would hold. I clipped in and climbed the remaining 20m to the platform.

Lakpa Gelu stands on the summit of Everest. I took this photo about 200 meters from the summit. It shows the summit cornice of snow. If you look carefully to the left middle of the photo, you can see former summit poles that have rolled with the summit cornice due to the extreme pressure of the jet stream that often descends onto Everest’s summit. (Jeff Shea, 1995)

The summit of Everest was in full view, shimmering, dream-like, about 100m away. I warned myself not to let my guard down. As a testament to the need for vigilance, a few days later Bob Hempstead slipped on this easy ground and rocketed head-first on his back to the brink of the North Face. Swiftly reacting, he caught himself with outstretched arms on rocks. He peered over his shoulder, staring down the awful 3000m precipice. Greg Child and Ang Babu found stray rope and pulled Bob to safety.

As I approached the highest point on the globe, I felt as if the spirit of the mountain touched me. At 9 a.m., Lakpa radioed, “T’ree people summit! T’ree people summit!” During 40 minutes of celebration and photography, I reminded myself that the day was not done. At least 15 people have died while descending from the top of Everest.

During the eight-hour descent I suffered extreme dehydration, which was made worse by the effects of the dry ambient air and bottled oxygen. When I tried to swallow, I gagged, then flew into a fit of dry retching. Later, the condition grew serious. I reached inside my mouth and extracted a strange brownish gel that had formed over my teeth and gums; I discovered afterwards that some of the enamel of my teeth had flaked off. The mixing bag of my oxygen mask became a deflated sack of ice. About 100m above Camp 3 I ground to a halt, my oxygen having run out completely. At 6 p.m. I laid outside the tents, stretched to my limit, reveling silently that I had made it. I spent the night without dinner, then headed to the North Col the following day.

After our expedition, at an American Himalayan Foundation event, Bob Hempstead and I found ourselves sharing an elevator with another Everest summiteer. We were shaking hands with Sir Edmund Hillary! Bob blurted out, “We summited Everest.” I naively added, “From the North Ridge!” A man of impressive stature, Sir Edmund smiled down on us, as if beaming approval on the progeny of his pioneering. But I sensed his mind was far away. Perhaps he was thinking about the speech he would give that evening, covering his climbing career and his school building program in the Solo Khumbu. Somehow I sensed that long ago he had recognized that reaching the summit of Everest was secondary to the effort of helping those people who had helped us to get there in the first place.

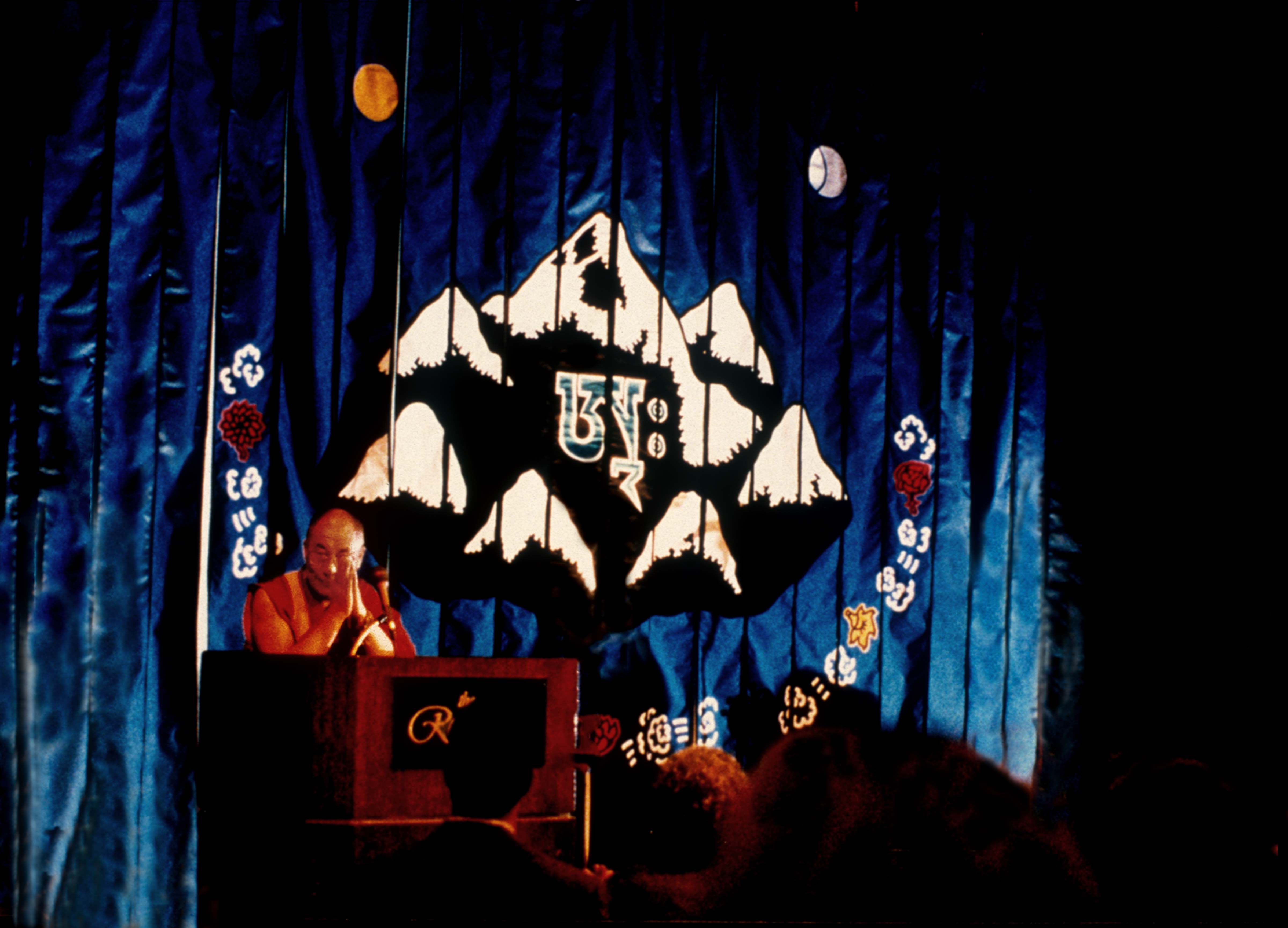

The thrill of reaching the top of Everest is equaled by the privilege of having been to Tibet, and I will never forget its landscape and its native people. Later that year, I dedicated my Seven Summits adventure to the Dalai Lama’s dream of Tibet as a World park, a wildlife refuge, and non-nuclear Zone of Peace.