Pilgrimage to the Taj Mahal – A Walk from Jaipur to Agra, 1984

Nepal, Bagmati Province (Zone), Solo Khumbu – 35mm film

Around the World 1982-1984 – Nepal

Mount Everest, shown in this photo, is not so far away from Pokhara and Annapurna, where the journal entry below begins. Although this photograph is not of Annapurna, it is nevertheless similar to the scene described below.

A Revelation – I Am the Universe (and So Are You)

January 1, 1984

Baidam, Nepal

The first thing of the New Year is that I let out a Whoop, a lone cry from my otherwise quiet self, laying in the night wrapped in down clothes on the temple island on Baidam Lake*.

*(also known as Phewa Lake)

January 2, 1984

Cottage on Baidam Lake, Near Pokhara, Nepal

The boat swirled around. I had moving visions of the Annapurnas backdropping Judith at the other end of the boat. When we got to the other side, we beached the canoe and walked to the cottage. Shortly after arriving, I sat down on the ground with a good view of Lake Baidam and the Himals. Here I sat for the sunset and pondered the mysteries of the Universe.

I asked myself “ridiculous questions” and got answers so deep I transformed into a believer. In between, I would sit and “see,” without thinking. Think/see/think/see.

The mountains seemed to have a soul of their own, so I wondered if they were not being as I was. Who was superior? They had pushed themselves up through geologic time to gain ascendancy over the lowlands and lower mountains of the world. But I have eyes, I can move! Yet who is to say that they are not cognizant in some way unknown to me? They see the sunrise first and the last of the setting sun. They stand staunch for millions of years, unmovable, but I am come and gone in a flit.

Suddenly, I caught a glimpse of the eternity of space and matter. Rather than feel shut off by my short time here, I felt close to the Universe. I felt part of eternity. In the recesses of my mind, a knowledge submerged now expanded into my consciousness for a revelating moment. It seemed staggering and yet so very natural. It seemed that I had always known the Universe.

Now I hesitate to deny the truth of my revelations however ludicrous they appear, because the feeling was so strong, and it seemed clear, as if God had filled my mind, and I saw as God saw. My imagination was free to run unhindered. I reflected that one of my goals was to live one of the most unimaginably exalted lifetimes in history. I wanted to live a billion such lifetimes, and I considered that this could be one of them. I felt like a prince, like a king, like a philosopher. I reflected that maybe all of my goals were taking place in different parts of the universe simultaneously. Maybe I was living other lifetimes right now, maybe I was a rock contemplating for a million years. Maybe I was riding on a comet. But because my desire was to live a human life, I, as my human self, could not have human knowledge of other existences. Just because I was unaware did not negate the existence of an expanded self!

Truly, when I had asked myself before the end of the year what would I achieve if I could transcend time and space, I was reaching beyond myself, beyond my own life and powers as a human, envisioning events that I will never experience as a human. However, in that moment, I broke a barrier of perception. By imagining that greater than myself, I caught a glimpse of reality greater than myself, transcending my humanness. Once the possibility was envisioned, it stunned my human mind into a sort of remembrance, and suddenly, my imaginings seemed a certainty, a reality! I knew a larger Universe than my human recollections would allow. It seemed I had returned to a state of natural realization that had floated around my earliest consciousness as a child. The possibility of other realities (greater, much greater, than my human existence) perceived with the same spirit that I call “ME” seemed ridiculous to be termed “possibilities,” for they were a greater certainty than my own human existence! I had “seen” all this.

Last year, I had written out my transcendental desires, and now had a gut level confirmation that they could be real. Could my desires cause reality, or could reality be reflected in my desires?

My imagination exploded. I thought of Being. I looked at the range of hills in the foreground of Annapurna, now black silhouettes against the pink snow of the distant mountains in the sunset.

Another “ridiculous question.” If I could be a segment of the hills in the range or to be the entire range, what would I choose? Could I be the Annapurnas? If I could be everything, would this not be more to my pleasing than to be part of it only? But, thought I, I would only like to be the good things. Then I reflected that all things are good. Maybe we consider actions as being bad or good, but objects themselves are good. My conclusion was that I would like to be everything in the Universe − the Universe itself!!!

Now I made a declaration that I cannot explain the “logic” of. I tried to reconcile that if I was the Universe, what was my physical body? What was, then, the purpose of my life? I thought: the purpose of my life is to see myself. By this I do not mean physical self, for as many say, this is only a vehicle. When I say “myself,” I mean the Universe, for I am that, I am the Universe, and by Universe, I mean everything that is! (Even if my normally conscious mind can’t see it, it can accept that it is there.) I, as the Universe, am thus employing my body to see itself in a new way.

These last points were somewhat muddled. But I felt, nevertheless, the following conclusion. I am the physical Universe: the word ‘I’ in this sense denotes my spiritual self. On the question of my physical self, to live the most exalted lifetime I possibly can is the focus of all my dreams. To grow as much as I possibly can is my strategy. I felt that I must prepare my physical body to be a conduit for the powers of my greater, physical Universal self. This stems from the idea that my physical body innately has limited capacities, but that it is possible to draw on greater powers, to funnel them through a properly prepared psyche, and release them in actions of goodness and superhuman power.

I felt and feel convinced of the immortality of my spirit and it’s ability to enter reality again in some physical way. I wrote: “The lifetime of this body is finite, but I shall go on and on”. It was a secure and everlasting feeling. Among my final conclusions as night set in were: “There’s not much time in this physical body, so I am compelled to use it to the best purposes. I feel as if the fact that my Time is limited in this life is my impetus to grow and to be good, my impetus to be simple.” I am not speaking in figurative terms about the whole matter of Being the Universe, but on the contrary, I feel quite clearly and sanely the things I wrote.

The idea of preparing your body and mind to receive greater powers: how would one do this? It seems obvious that one would try to tell the truth, so that truth would flow through your mind, that one would try to be peaceful, so that peace would flow through your soul; one should seek to have right conduct (along the lines of Plato/Socrates) so that the body and mind should enjoy harmony and thus be accepting of universal harmony; one should develop the body and nourish it, so that one can enjoy the vibrations of vitality inherent in the universe. One should learn and grow, seeking to expand, so as to allow a greater volume of light (or power) to flow through one’s self at an increasing rate. All these things might be ways to prepare the human entity to receive greater power into itself.

Thus, sitting still on my perch above Baidam Lake, I peered into the mysteries of life and felt surprised at the relevance of my answers. I felt strongly that I was the young king experiencing revelations at the proper and chosen time. I felt the intensity of my life in the light of a millennium of millenniums and beyond. They were wonderful and serious sensations! …

Judith came up to me, as it was time to eat. She asked me how I felt. I replied: “Like a king, like a god!…” We ate a Nepalese dinner with the cottage people. Then she and I retired to our room in the otherwise vacant building down the hill towards the lake. Judith’s period had come in the afternoon, so I was able to come inside of her. Our lovemaking was beautiful and, as usual, full of lust and passion.

The Walk Out of Jaipur on Foot – Village Life

January 18, 1984

Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

One of the most amazing facts about today was that, for the first time in my life, I legally bought opium and ganja! This is the only place I’ve ever heard of where you can buy opium on the streets! Along the main streets, you can sometimes find a wooden shack which they call “government shops.” I bought ten grams (or one tola = 11.6 grams) of nice sticky opium for fifteen rupees (just under $1.50, or fifteen cents per gram) and the same amount of “grass” for five rupees!

Judith and I were not able to find a suitable ground protector, so we will leave without one. We looked at a few stones but had no luck really, and I wasn’t really in the mood. I posted letters to Gam, Kelly, Cappa, the US Embassy Kabul and Mom. I felt crummy by the time we left the city, but as soon as we started up the road to

the castle, I immediately felt better. We rose above the clamor and dust of the city into the pure heavens. When we arrived, we ordered dinner. We didn’t eat till 10:30pm and slept after that.

January 19, 1984

Slept someplace North of Jaipur in a village in a “dela” (thatched bed on stilts with roof), India

Awoke with Judith in the former Maharaja’s palace before the sun rose. We enjoyed a joint of marijuana and hashish while watching sunrise from bed.

Jeff: The sun rises on the rest of our life on the morning of our first day of the pilgrimage to the Taj Mahal.

Judith: The sun is so beautiful! Have you ever seen a more beautiful sunrise? The sun is purple, blue, yellow around, and white inside. [Ed. Note: In reviewing this manuscript, the preceding line prompted me to compare Judith’s description of the sun with the photo of the Pulsating Stone on page 387. Oddly, her description was quite close to appearance of Stone, which I photographed 21 years, 11 months and 1 day later.]

Jeff: The great pool (there is a rectangular pool of water in Jaipur, very large, easily seen from our castle window) below us reflects our souls in the distant sun, and they shine back to us in glimmering brilliance.

Then she and I proceeded to make love, enjoying it to the utmost, it being one of our usual wonderful experiences… We were given two buckets of hot water. She and I bathed for the last time at the castle.

We departed. We walked along fortified walls that extended for a long way from the castle… to the opposite castle and then down into northern Jaipur.

India, Rajasthan Province (State), Jaipur – 35mm film

The view as we headed down from the former Maharaja’s palace.

On the road to Alwar, the “Delhi road,” we saw the first elephants, which were tattooed with bright colors on their faces and ears. Amber Fort was colossal and magnificent. Given two red carrots by men with loads of them. Decided to walk eastwards and go off the main road. Walked through a nearby dry river gully, talking to Judith. She told me how she broke up with former boyfriend Manfred.

We proceeded past villages of children showing great excitement at our approach. It grew dark. We came upon a kind young man named Ramkaran. We were invited for tea. We sat on the ground in the dark. The tea was sweetened with ghir, palm sugar. Then milk was brought, sweetened in the same way. It was very delicious. We asked for a place to spend the night. We were shown a “de-la”, which was a roofed bed in open air on stilts; the bedding was made of twine. We showed great thanks, clasping our hands in prayer-like fashion, as was the custom. We sat with the men. They talked peacefully amongst themselves. After a time, chapatis of wheat and supaji (a soup-like vegetable dish) were brought. Judith and I ate heartily.

The father was introduced to me.

Father: Namaste!

Jeff: Namaste!

Father: Namaste!!

Jeff: Namaste! Namaste!

Father: Namaste! Namaste! Namaste! Namaste! Namaste! Namaste!…… (getting quicker each time)

Each time Namaste was said, our heads shook from side to side. The final time, the result was ludicrous! Everyone broke up laughing.

He and his family invited us to sleep on their farm.

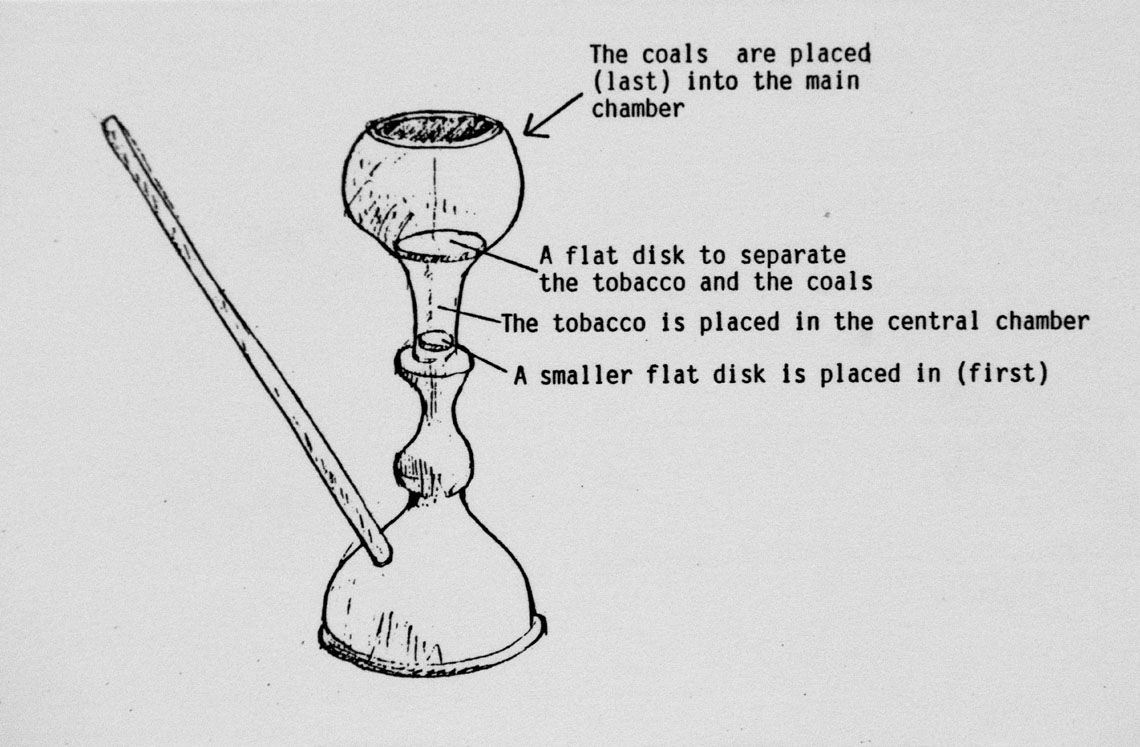

After dinner, the pipe was brought out. The pipe was of the construction shown in the illustration below.

Illustration of Rajasthani Water Pipe – (Illustration by Mike Taylor based on description by Jeff Shea)

A small flat disc of rock was first placed in the pipe. Then local tobacco was put in. Then a larger plate was used on top of the tobacco. A small fire was made so that its burning embers could be placed in the top chamber, as shown above. The embers from the fire were put in the pipe, thus separated from the tobacco by the rock disc. The pipe was passed around and around between the men. They wore turbans on their heads.

We sat in a rough circle. The magical rising of the full moon appeared in the East. Judith and I were “awesomized” to the maximum. A magical evening to cap a day with a magical morning. “Ottar-North, Purake-East; Dashim-West; Darkshingh-South” – the directions were explained in the local language.

Many “don-e-bat’s” (thank you’s) went back and forth between Judith, the people and I, especially with the father, a good-natured farmer 45 years of age. I said a final goodnight and everyone went off the bed. Judith and I retired to the “dela” to sleep in our sleeping bags.

In the middle of the night, we awoke with a fright!! I thought, in my dream-like state, that we were being attacked. Judith screamed! Our senses came to us. There were men in the moonlit fields, talking, with responses coming from men in the bush house adjacent to our dela. A man in black sat in the field while a man in white stooped to the ground again and again, planting or tending to the ground. It was surreal: men in the middle of the night ritualistically sowing their field according to ancient knowledge.

India, Rajasthan Province (State) – 35mm film

January 20, 1984

Slept at farm house two kilometers from the Delhi Road, North of Jaipur, India

I woke to the sounds of birds. Amongst them were gray-brown quails half a foot long with hues of pink, purple and blue in a subtle blend.

The men were already smoking their pipes early in the morning. They watched as we packed.

Jakdeesh, the boy who speaks the most English, told Judith and I to wait for breakfast. A brass tray was brought with hot milk, lumps of ghir, chapatis and supaji.

We took our leave. We were accompanied towards the main road by Ramkaran. He said, “I am a poor man.” Judith and I left a pen and a cup as a token of appreciation. Then we headed northeast through fields.

We stopped to take off clothing as the hot sun rose in the sky. We stopped at a sandy road with mud walls on either side. Camels came by pulling carts. A herd of goats passed. Judith and I continued eastwards and northwards, traversing fields, walking on narrow mud mounds lining cultivated plots. We found a sandy road, and then crossed uncultivated desert scrub into and out of a gully. We passed over a hill. Judith and I made love inside a sleeping bag under the hot sun. Then we walked down and up again to a bluff.

We sighted a mountain and headed towards it, thinking it to be in the direction of Sariska. We crossed over dunes of desert sand into a village on a plain. The children were more quiet there than the children we’d encountered along the road.

We observed how the farmers used their wells to irrigate the fields. Water was pumped by an electric motor up a pipe, then spewed out into a pool. From there, it flowed into irrigation canals made of small banks of mud.

I asked permission of a man to dunk my head in the water. I took a quick ‘refresho’. I asked him which way Ghiri was. I repeated the question again and again. On the fifth time, I discovered that the man thought I’d said Jaipur and that he didn’t know Ghiri at all. Judith and I continued along, trying to communicate with the locals but to no good end, as no one could speak English. I approached a kid to ask directions. He walked briskly away, afraid of the strange sight of a foreigner.

We were without food or drink. The countryside was flat with hills in the distance in all directions. I lamented that I had no compass, for without it, I said, we had no way of telling directions. The best thing to do was to go back to the main Delhi road, which we knew to be heading north.

We asked for tea in the first village we came to. (It always took a few tries to get what we wanted. At first, they never had anything it seemed, except for maybe tea.) Further down the road, we got milk and tea. We offered money, only to be refused – it was the custom to help travelers along.

Once we were back on the main road, the mountains made sense again. I could make out where we’d gone wrong.

We met up with a link road. A small town. We stopped to shop for food. The people crowded in close to look at us. Even after my repeated requests for them to back away, fifty people were still confining Judith and I to the point we could hardly move. We bought peanuts, tomatoes, bananas and onions, then went to a tea shop to have hot milk. The children so crowded me that I got the slingshot out of my pack and started slinging peanuts at them. They ran. Judith and I finally split, glad to be off by ourselves again. But we were followed by two English-speaking boys. They were obnoxiously friendly. They were insistent that Judith and I go with them to their village and stay the night there. Judith and I politely insisted that we must keep going. But we were finally persuaded to go to a nearby farmhouse to eat. I was so tired that I sat and said little when we arrived. Delicious warm corn chapatis were brought with milk and supaji (“subt-je”). I fell asleep right where I was after eating.

January 21, 1984

Slept in sand on the side of a small road just before Dola, Rajasthan, India

I was up when the sky turned pink.

On the Delhi Road, we found a place to get fresh milk. We roasted tomatoes on their fire and the men there taught us how to smoke tobacco from their chillum. The tobacco made me feel sort of dizzy but good.

We walked off the road and cut across fields. We were shown a dirt road by a village man.We met up to the main road again. We bought a papaya and I took a picture of yet another castle on a hilltop. While we walked to a place to eat the papaya, a solution to our navigation problem occurred to me: the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, so at midday in the northern hemisphere, the shadows should be cast to the north. Also we should be able to correlate the length of the shadows with the hour of the day.

Judith was anxious to go cross-country. I agreed with her as there was no longer any reason to stick to the road, for we had fruits and vegetables and a way to determine direction.

When we came to a sign (“Tala 8km”), we cut off northwards from the link road. We came upon a village where the irrigation was done with the use of cows. There were three pairs of cows. Two teams worked while one team rested. The harnessed cows walked down a grade, turning a water wheel. At the bottom of the grade, the cows were released, then walked back to the top by a man. At first, the men refused to let us shoot photos, but soon they were vying for the camera’s attention. There, we saw little boys and girls with no bottoms on but with shirts on top. They had keys or bells hanging on strings near their genitals.

India, Rajasthan Province (State) – 35mm film

Rajasthani woman with anklets and tattoos fetches water.

The women wore silver jewelry on their toes and ankles and around their wrists. The silver jewelry was studded with clear, faceted stones.

Walking through the fields, we soon saw another new sight. Men were digging a well and using camels to haul out the dirt in much the same way that they used cows to turn the water wheels. I looked into the pit and saw four men digging, filling the basket with dirt. At their feet was water, so I figured the entire countryside had a water table underneath it. They would not allow Judith to see into the well, as they said it displeased God.

India, Rajasthan Province (State) – 35mm film

Water for irrigation was pumped by camel and bull power. This process was silent. In “modern” villages, electric pumps were used. The pumps made incessant, loud noise.

Further down the road, we saw yet another well powered by animals. On the left, cows were employed, and on the right, a camel was used.

Further northwest, we came to a village: Syampura. The villagers gave us tea. Two men, who were teaching the children outside, talked to us in poor English. The village’s “big man” − who they said was very wealthy − had gold earrings.

We proceeded then rested by a dirt side road. We discussed whether or not we should walk eastwards towards a white structure across the plain. I suggested it could be a castle or even a temple. Judith thought I was imagining. To our surprise, a bus came down the road and stopped. The men told us that it was a mosque in the distance.

Judith and I walked across a large gully to the mosque, which was in a large village. We sat at a teashop with a horde of people around us. We were quite hungry and kept asking for chapatis even after we were told that to obtain them was not possible. However, one nice man took control, and soon, chapatis and supaji began to arrive from neighboring houses. The villagers took delight in watching us satisfy our ravenous hunger. I drank tea after tea. One old lady brought us fresh eggs, which they boiled for us.

We went to the mosque. We stood on the roof. It was lined with burning torches. We looked out in all directions in the last of the day’s light.

India, Rajasthan Province (State) – 35mm film

We were invited to stay, but Judith said she didn’t feel free there, so I said, “So, let’s go be free.” (Sometimes it is hard to turn down the good intentions of the local people, but I think it is often best to do so rather than infringe on both your freedom and theirs.) We were very happy to have gone. We merrily walked along in the darkness, thankful for the full bellies we had and the kindness of the local people. We had a stop. I discovered the eggs had already gotten smashed − not cooked enough. We passed a village, listening to children sing.

Further down the road, we found a sandy place just off the road and set up camp. We got in our bags. The waning white-yellow moon arose, near-full.

January 22, 1984

Slept on asphalt road north of Pratabgaard for three hours; later slept on pile of bundled reeds seven kilometers south of Thana Gazi, Rajasthan, India

Morning. “It’s raining,” exclaimed Judith. Only a light drizzle. We got up and started walking. It was 5:30am. Soon we reached a fork in the road. There were some teashops and a small city behind an old fort on a hill. The people there made us tea and hot milk.

We went up to the castle and looked out over the land. Judith discovered that she’d left her ring down at the teashop when washing, so she left to find it, and I remained on the castle wall and smoked the joint I’d prepared last night of Rajasthani ganja and hash. The bus booking agent came up and sat on the battlement and showed me direction of Pratabgaard. He said that the road ended here in Dola (a quite dirty village) and that we would have to cross the desert on a sand road to get to Pratabgaard. From there, there was a link road to Thana Gazi.

Meanwhile, Judith had not found her ring. She became frustrated by the bus driver who wanted to buy her watches, so she left and sat down a few hundred yards from the teashop. She’d given the bus booking agent a penny from USA and I explained the meaning of all the mottos (except E Pluribus Unum, which I don’t know the meaning of) while others looked on.

The teashop keeper wanted something from America, so I gave him a TIME Magazine. He also wanted a photo of himself and his teashop, so I took some (28 mm) photos with the old fort in the background. (They it was 1200 years old, but I doubted it highly.) The shopkeeper was missing his leg above his ankle, and I thought it “Bob” (i.e., admirable) of him to take two of the four pictures deliberately showing his stump − it seemed that he was proud of it.

India, Rajasthan Province (State), Dola – 35mm film

Pratabgaard shopkeeper, proud of his amputated leg, with fort behind.

I did some washing and left, figuring I’d find Judith along the road. On the way out of Dola, I was joined by an English-speaking Dolian who was very congenial. Soon, a boy came running up to say that we had to go back to the teashop because someone had found the ring and would only give it back to me. We were informed by an old man that Judith had gone off towards Pratabgaard accompanied by two village boys. I figured it was best to go fetch her ring.

There was an old man sitting on a bench at the teashop. He wanted fifty rupees for the ring. I said No. Soon the boys and men were giving him a hard time, telling him to give me the ring. Finally, the English-speaking fellow’s father came up. The old man gave me the ring when the boy’s father told him to do so. I got change for one hundred rupees and offered him ten rupees but he wouldn’t accept it. I asked for silence from the crowd and said that in my country, it is custom to give a reward, but I was told I should follow their customs. I thanked them and went on my way.

The English-speaking fellow gave me directions (left at the Banyan trees) and taught me the phrase “How do you say…?” in Hindi: “Ap kyah ke-te-tu-hum?” and Rajastani: “Te ka-e ko-cho?”

As I walked along, I let out yells so if Judith was sitting off the road, she could hear me. I passed one of the boys who’d been with her and he nodded to my questioning motions. But all the other men I saw seemed to know nothing of her whereabouts. I studied the sandy track for her footprints. I estimated they were 45 minutes old and I was going one third again as fast as she was. I spotted a form ahead. It was Judith. She was very pleased to find me and her ring. We sat on the road, picking brambles out of our sweaters. She prepared a salad of tomatoes, red and green onions, white radishes the shape of carrots, bananas and peanuts. After our repast, we walked towards Pratabgaard.

Pratabgaard Fort was classic, sitting above the town high on a mountain with a 45-degree slopes on all sides. They had a loud, constant whistle coming from a motor. I wondered how they could tolerate such a continuous nuisance. I thought, ‘Even if it is for electricity, so what! I’d rather do without it!’

We had tea and milk.

On the road out of Pratabgaard, I saw beautiful green parrots and blue peacocks. The road was quiet − just an occasional bus. In the glow before sunset, I took my guitar out and played as we walked, gathering strange looks from some. Two men in camel-driven carts offered to give us a ride, but we declined. The distant castle became a small silhouette at the end of the valley, backdropped by slashes of blue and black across a pink-banded sky. Walking with my guitar, I imagined a whole such life, wandering all over the world with women, practicing all the time.

Warm clothes on, we continued over the hill and down to the next valley, which spread out before us in near-total darkness. We wanted to eat, even if it meant walking all the way to Thana Gazi, 14 kilometers distant.We walked towards firelight coming from a village. When we arrived, I sat by the fire. After a rest I said: “Rupees I give you for food, chapatis, dood’h (milk).” We were brought to a place where a fire was made. Chapatis, warm milk and supaji were brought to us. They invited us to stay the night, but we insisted on leaving. We gave them some fancy blue aerogramme paper and thanked them sincerely. They refused, as so many Rajastani do, to accept the money (ten rupees) we offered.

Just before moonrise, we laid out the tarp and sleeping bags on the asphalt road and listened to the sounds of the night. A white horse came wandering down the road, startling us. We watched the moon rise majestically at

11:35pm. Then we fell asleep right on the road. Luckily no cars came by! At 2:30am, we were up and walking again. It got a little hard going. At 4:30am, we pulled off the road. I made a bed of bundled grasses. It was very comfortable. We fell asleep.

Sariska Game Park, the Watchtower and Tiger Eyes

January 23, 1984

Sariska, Rajasthan, India

In the morning, we were woken by men with their cows. They didn’t bother, so we just went on sleeping. When we got up they came to us and tried to speak to us but we could only say, Thana Gazi. Namaste and Donebat. We walked on past a village where the people were friendly. We saw yet another castle. This marked Thana Gazi and the bigger road. We were too closely followed by three curious boys.

We bought fruits in Thana Gazi and had lunch. There were eighty people about us. I utilized my slingshot to drive them away. We walked towards Sariska, only eight kilometers away. Judith and I stopped and had a chat and a fight, then made up. Happy as two lovebirds, Judith and I walked all the way to the Tourist Bungalow while she talked about love affairs. About two hundred monkeys swarmed the road and the trees.

We checked into a double room at the nice hotel where a bunch of Europeans sat on lawn chairs looking like they died years ago, all pale and unhealthy. I put Judith on the bed and we had excellent lovemaking. We stopped

“till evening,” then got up and went to dinner. I spread out the map of India, and I saw that our proposed trip to Agra was a certain percentage of a trip across all India. I fantasized about rafting from Agra to the Bay of Bengal on the Ganges and its tributaries. I thought about doing continuous links in an around-the-world trip over the course of my life.

It took some time and still no waiter or food. I walked back into the kitchen and said: My name is Jeff and I am from America. I began to explain what I would like for dinner. The outcome of this and subsequent visits to the kitchen was a relatively fabulous meal: two plates of mutton in sauce, fried dahl, vegetable cutlets, French-fried potatoes, chapatis, and carrots fried in butter. (I peeled and diced them myself.)

Well satisfied, we returned to the room. Judith waited for me in bed for two hours while I did chores. She sang “J Ran, J… J… Ran…” over and over. I blew out the candle and lay with her.

January 24, 1984

The Watchtower, Sariska Wildlife Reserve, Rajasthan, India

I found out that we could spend the night in the Watchtower, a place used for observing animals, eleven kilometers away towards Thala, on our route to Agra. I arranged for us to spend a night there. We left for it about 5pm. On our walk to the Watchtower we saw monkeys, many deer, cows, and two wild pigs.

Dusk. We continued on, talking about tigers. I expounded on what I had learned about them from the book on tiger hunting. We arrived to the watchman’s house at 8pm. We convinced him to make some tea and gave him a cigarette. He took us down to the Watchtower. The man left us. Judith and I ate eggs and an apple, after which I promptly fell asleep.

I thought the Watchtower would be twenty feet in the air, but in reality, it was low to the ground. Its roof was only four feet high. The walls were a foot thick. As soon as we got in, I took my flashlight and shined it at the water hole. It met a pair of green eyes. The eyes stared at the light and then moved away. From what I’ve read it could have been a tiger.

India, Gujarat Province

Many years after seeing the green eyes of a tiger at night from the Watchtower in Sariska, I had a chance to see two of the five big cats in India in broad daylight. The Gir Forest in Gujarat Province, just south of Rajasthan, is the last remaining refuge of the Asiatic lion and the only place outside of Africa where lions are found. The Indian Leopard shown here is classified as Near Threatened.

January 25, 1984

The Watchtower, Sariska

Rajasthan, India

2:30pm. The watchman came and told us that there was a tiger here last night. Two foxes came to the waterhole and the peacocks cleared out. The fox had paranoid eyes as he drank and ran quickly away. The watchman came by with a “ranger” and they showed us the tiger tracks. I shot a photo. So far today, we’ve seen nilgai, deer, spotted deer, parrots, peacocks, many smaller birds, monkeys, and a water buffalo.

January 26, 1984

Village Six Kilometers after Thela on road to Rajgarh, Rajasthan, India

We walked on to Thela. As soon as we got to town, we passed a schoolyard where the children, upon seeing us, began to flock towards us. Since I wanted no repeat of former scenes, I immediately intended to drive them away and made every effort to be unreceptive. I took to picking up small rocks to drive back the increasing mob. We sat in a teashop. I rushed out a few times to show them I didn’t want them too close. (Despite appearances, I was really in a good temper.) The shop owner chased them back with a stick and upon seeing my pleasure was encouraged to do it again. Soon, the mood became happy. I had my canteen filled with hot milk. People boiled potatoes for us. I had multiple teas. Then they started passing the chillum around and I am afraid I smoked too much, along with a few of the many biris offered. Before we left, an old man played Judith’s flute expertly. There was a huge crowd of people standing in the road. We took pictures of them as we left.

India, Rajasthan Province (State) – 35mm film

Some way down the road, accompanied by a number of boys (which Judith wished would leave), we came to a swimming spot. I took a dip, while Judith continued to a more secluded spot down the road. When I came up to her, I saw that she was swimming only in panties. Men eagerly waited for her to get out of the water. I said, “Don’t stare at the missus.” I yelled at them to move on. As they did not respond, I picked up some rocks and charged at them. They fled and I kept after them. They were undaunted. I chased them further down the road at a full sprint. I ran back to Judith, and I told her that if she swims topless with a group of men around again, that she’ll have to defend herself by herself. I took another swim, but after my sprint, I felt suddenly weak and chilled.

At 4pm, we continued down the road. Three boys stared at us. They would not leave us alone no matter what we did. So again, for the third time today, I picked up rocks to keep them away. When I got to a teashop, I grabbed and pushed one of the boys who’d been taunting us. The people tried to calm me. They urged us to have tea, but we just went on our way. We walked for another half hour or so and stopped at a rock to watch the sun set.

I was feeling chilled. There was a village across a field. I asked a villager if we could stay the night. He led us to his place. He showed us a bed*. I fell on it immediately, exhausted. The people stared at us and crowded around. Judith was freaking out and said so. As a solution to make them go away, she got in bed with me. They continued to stay around us until they finally were told to leave by some men.

*(The bottom end of these “beds” have wide gaps between the strands, so your feet slip through if they aren’t already hanging off the bed! These “beds” are only five feet long and uncomfortable for me. As the locals are sometimes fairly tall, I can not imagine a good reason to prevent them from making a comfortably-sized bed, a place where they spend one third of their lives (e.g., 10:30pm – 6:30am).)

Later, tea was brought, then milk. I was feeling pretty bad, burning up. The people started crowding in again and yelling. That’s the way Indians talk to each other − very noisy. I needed fresh air and quiet, so I jumped up and went out and lay outside the circle of men around the fire on the ground. I imagined that everyone thought this was a strange thing to do. But I was burning up and I wanted to cool off, lest I destroy my brain cells! I was a bit delirious. I thought I was going to die, and I lay in the dirt awaiting death. I asked forgiveness from God and wished for entrance to heaven.

They brought me supaji and chapatis but I ate only a few bites. Feeling a bit better, I went inside and lay down. All through the night, the men in the three–sided room with us were talking, coughing, moaning and turning in their sleep. It was a broken sleep, uncomfortable and feverish. In the wee hours of the morning, I crawled into Judith’s bed. We awoke before dawn.

January 27, 1984

Rajgarh, India

Judith and I got up and packed. We gave the villagers a mirror, a can opener, and a nail clipper for gifts. They made morning tea. We thanked them.

The sun rose over the hills before we reached the main road. I was feeling weak, but I kept on. Just after we passed a sign saying it was thirteen kilometers to Rajgarh, we stopped. I lay on the roadside in the dirt in the sun.** I fell asleep while Judith made a salad of bananas, apples, tomatoes, peanuts and onion. After eating, we left.

Each step was a burden – unusual for me. We found a water-well with a motor pump where the locals were bathing. Judith had to clean her feet so that she could remove the splinters she’d gotten yesterday at lakeside. Again, I rested in the heat of the sun.

On the way, we put the potatoes and unwanted articles in a bag to lighten our load, intending to give them to the first locals. As we came up to a group of women, Judith went towards them. They backed off, fear-stricken.*** She left the bag on the ground.

I ate some salt and drank plenty of water, thinking part of my weakness might have come from loss of salt and fluid. We walked past Kilometer 4 (to Rajgarh). We lay in the dirt in the sun fifty meters from the road. I fell asleep. Hearing voices, I woke and looked up to see villagers staring at us. They made no sign to leave. I put my finger to my lips and “sshhed” to let them know I wanted quiet. I closed my eyes and rested. They moved off. Next, a larger group of people came close by and stared and made much noise. Men six-strong advanced and stood within ten feet of us, staring dumbfounded. I sat up. Judith and I left and walked into Rajgarh holding hands (as we often do when walking along).

When we got to the center of Rajgarh, we asked where a hotel was. We were led by an untrustworthy-looking lad to the tourist “guest house.” As we walked, the lad shouted with glee to the shop owners. Soon there were at least fifty – and maybe as many as seventy boys – following us and making much noise. They followed us in to the guest house. Noise, bedlam, chaos. Judith and I were led upstairs. We sat on the floor of the mezzanine for an extended period waiting for them to show us a room.

I had walked 18 kilometers with a fever and 35-pound pack (after potatoes were jettisoned). I was so weak that I cared nothing for the noise and was content to sit. Judith, however, suggested we leave. A boy sat close to her. Then I heard her say: “Hey, don’t do that!” She pushed him. Knowing that she wouldn’t do that unless he bodily “touched” her, I grabbed him and gave him a mighty toss that sent him hurling away, and only with great effort did he succeed in not landing on his face. This action caused a great stir. We repeatedly asked the men to close the gates to keep the throng of boys out. but though they seemed wanting to please, they did not oblige our request.

**(The Earth is neither unclean nor uncomfortable.)

***(These people, as far as we can make out, might possibly be herders, maybe living a nomadic lifestyle. They can be seen on plains with their livestock against a backdrop of mountains.)The doctor’s charge for the house call was only ten rupees (= $1). After having a glass of sickeningly sweet milk tea, I went to sleep. I tipped the man five rupees, which seemed to both please and surprise him greatly! During the night, Judith let me use her sleeping bag – in addition to my own – to keep warm and she used the blanketing provided to us for herself. I roasted, sweating from my own heat.)

Judith and I were given a room. It was bare except for a table-like bed of wood without a mattress and a “dela,” the cot with a wooden frame and a web of strings.* I immediately lay down, exhausted. The noise outside was a roar. The children banged on our door and on the shutters. They crawled up to the grilled vents to peer in. I could not imagine why they were allowed to do so. The boy who’d brought us to the hotel said he’d get us food if we’d give him ten rupees. After giving him the money, I realized it had been a mistake to give him money beforehand. He left, came back with 5 rupees of food and was not seen again. Judith went out to get some food and a doctor.

The doctor came and checked me. According to him, I had a 102 degree fever and bronchitis. The doctor said I should be better by tomorrow, and he prescribed some medicine. He was very helpful. The doctor appointed one of the hotel men to fetch the medicine, milk tea, and biscuits. I also communicated through the doctor that I’d like to have mats to make the beds more comfortable. With the mats and beds, the room price, the doctor said, was to be only 8 Rp., not the 25 Rp. that the guest house staff had quoted.

Our room was “conveniently” situated adjacent to a vacant lot, which happened to be the local pig hang out. Through-out the evening and night, from our room, we heard their sweet music, as they rooted, their melodious fighting, and their harmonic grunting. Funny, Judith thought it sounded terrible!

January 28, 1984

Rajgarh, India

They brought tea in the morning. The man who fetched my medicine last night brought milk, dahl, chapatis, oranges and apples. During the course of the day, he sought out and found a replacement bulb for my flashlight. For all this, I tipped him another five rupees (=50 cents USD), the great magnitude of which astounded him, I think.

I lay around and read about Tiger Hunting and I wrote. (I respect the author of Tiger Hunting but he’s still f_____d for shooting so many tigers.)

During the day, about twenty children wanted in. I opened the door, even though I was very tired of the many, constant disturbances. When I saw they came on pretense, I closed the door. They pushed it open. I shut it hard. They started banging on it. It was time to teach them a lesson. I decided to catch the first one I could and use him as an example. I ran out in my long johns (despite the fact that my privates were hanging half out). They got a good head start on me and I had to run out in the street to get one of them. I picked him up running and tossed him to the ground (lightly so as not to hurt him but in a way so as to scare the hell out of him as all looked on). He had his schoolbooks in his hand and I grabbed them from him and dashed them to the ground. I walked back into the room, I turned and pointed at the mob and said, “That will happen to you too!” After this incident, the hotel keeper was “miraculously” able to lock the gate – something he had previously failed to do despite my repeated requests – and aside from the short hubbub immediately following the incident, we were thereafter granted some peace.

A gentleman (in the true sense of the word) who had helped Judith find the doctor yesterday came by to look in on me. He invited us to dinner. He was so kind, I could not refuse, and so at about 4:30pm, we all left for his house. It was a very pleasant time and a delicious meal: rice with butter and powdered sugar, vegetables, pickled (strange) berries, chapatis with butter, a salad of cabbage, onions and tomatoes, chilied lemon peels, chilied pickles and a few other dishes. He invited me to come to his daughter’s wedding. Judith gave his daughter a digital time piece. We thanked him and his family and left.

Back in our room, I was happy to have rest and fell fast asleep. I woke to see sweet Judith hovering over me in the darkness. She wanted to come into bed with me. Now that I was awake, I was in an amorous mood. But then she dozed off to sleep. My advances proved to be in vain. I lay back. I realized I wouldn’t be ale to sleep so I got up and went to my bed and broke out my guitar and had a go at it in the darkness.

Later, the pigs in the lot next door started making an incredible racket. It was amazing how much noise they made! It seemed like the male was trying to force it on the sow. Then there were territorial fights and beatings. The men in the other room began making a lot of noise. The place was a madhouse!! When I went over to tell them to quiet down, I saw that these three poor guys were only making the best of the fact that they too could not sleep. They invited me in for tea. Judith came in and left. They had their businesses in this room. They fired up the cotton candy maker and gave me some. One guy worked on cutting and pasting glass into small shrines. He placed cheap paper prints of Hindu religious scenes in them (the kind where the people are purple). (I’m sure glad that I don’t live like these guys. All three sleeping together − waking at 5:00am to do their work. What a life. I could never do it I think.) I went back into the room and fell asleep after talking with Judith.

More Confrontations with Curious Villagers

January 29, 1984

Abandoned, crumbling well building near road some kilometers outside of Rajgarh, India

We awoke. Despite the fact that I was deathly ill, in the morning we decided that we couldn’t spend another night. There is no rest here. People by day and pigs by night.

Judith and I packed and paid our bill in the afternoon. Prior to leaving, she and I made love. It wasn’t so great. I feel sort of weak from this bug… (I felt bad for finishing too soon. I feared I was not enough for her… On a rational level, it’s silly to think this way because Judith and I have had such superb sex mostly… When I get feverish, I get delirious.)

As we went down the street, we tried to ward off the children, but to no avail. We met a man named M. Paresh. He had us to dinner. He seemed surprised we were leaving town. When we told him of the noise at the hotel, he offered to let us stay at his place. He seemed disappointed when we declined his offer.

During this discussion with Paresh, the crowd increased in number. Judith and I tried to escape from Rajgarh. I wanted peace. The throng of kids caused me misery. It pissed me off that they crowded around me. I gave them the thumbs down. Despite my attempts to discourage them, they began chanting, “I Love You, I Love You.” I supposed those words were intended for Judith. This bugged me. The crowd followed and harassed us, and, of course, the more they bothered me and I showed my displeasure, the more they were encouraged. Although I made threatening gestures in an attempt to disperse them, they remained unafraid. I threw my pack down and raced till I caught one of our tormentors. I didn’t want to hurt him, but I want to scare the hell out of him. I tossed him around while holding on to him. I grabbed him by one arm and tossed him over my shoulder like a sack of potatoes. I brought him out to the street and hailed the other kids. I shouted at them. They ran screaming. The kid I was holding cried for mercy. I let him down and walked off.

Some nice men out for an evening ‘constitutional’ erroneously informed me that Agra was about three clicks (i.e. kilometers) away. Meanwhile, off on a distant hill, a regrouped battalion of youngsters chanted, “I Love You, I Love You.”

I stopped to photo an incredibly colorful bird, but a crowd formed. Judith refused to watch my bags, so I abandoned the effort. As I put my camera away, the people holding their bicycles stood staring like stones. In an effort to intimidate them, I walked up to them. “What do you want?” I made gestures to provoke them to move on. They went off but made their inevitable regrouping not fifty meters down the road!

I found Judith. I said, “Let’s get off the road completely.” As we headed over the rocky hill, the congregation’s eyes followed us from the road, no doubt intrigued even more now by our seemingly irrational behavior (i.e., of walking off the road.) In daylight’s last hour,Judith and I parked our butts against some rocks. We ate fruit. We walked back to the road. Judith felt sick. We stopped and she lay down. We resumed walking. After a time, we came to a village with lights. We got some good hot milk and some carrots. One man invited us to stay in his house but was persistent to the point of harassment. We declined and continued down the road in the darkness. Another man asked us to stay with him. Judith reacted negatively, reminding me of all the people and noise there’d be there. Rather than listen to her complaints, I returned with her to the road. We were tired. We came to a well house. We stopped for a rest. I suggested we stay there, but Judith curtly said No. She explained that the place just didn’t give her good “vibes.” This irritated me. I told her so. I gave her a piece of my mind as we walked on.

The longer it took to find a place, the more upset I became that I hadn’t insisted on my idea of staying at the well house. I asked her to look at a place to possibly sleep. She sprained her foot. We walked on and found a crumbling old well house that was suitable as a shelter for the night. I tried to find hay to lay out but only could find hard dry reeds, which turned out to be even more uncomfortable than stone. It was like sleeping on railroad tracks. Ugh! Before I slept, I told Judith I loved her, but all I got back was a vibe that said: So why don’t you show it rather than ragging at me? And I couldn’t really blame her.

Diary, I’m just living my life, and all these frustrations are minor. We’re only human. Just got to try to keep getting on peaceably and as best we can. These are rough conditions, I think.

Judith’s Injured Foot Becomes Worse

January 30, 1984

Roadside village six kilometers from the main road leading to Mahuwa, Rajastan

I watched the sun rise. We got ready. Judith seemed to be in pretty good spirits, but her foot was bothering her. She asked for advice. I felt her foot. If it’s only a sprain, then walking on it shouldn’t hurt her, I told her. We came to a village and had tea and hot milk. On the way out of town, we were followed, even though we asked the onlookers for solitude. Judith suggested we run, which we did. Doing so, however, resulted in her injuring her foot. Thereafter, she began having serious trouble walking.

We came to a town. Ten or fifteen people followed us closely. Judith could barely move because of her foot. I repeatedly asked the crowd for room and solitude. They seemed indifferent to my requests. One boy, my height, seemed to be particularly enjoying our frustrations. I calmly walked up to him. I grabbed him and flung him with one hand, whilst I remained nearly motionless. He flew at least six feet away and landed on the ground. (I was surprised at the effectiveness I achieved through such a calm effort, concentrated with determination.) His bicycle fell down. Other bicycles fell to the ground too as their owners made a rapid departure. Judith and I walked on. We proceeded undisturbed from then on while the would-be pursuers looked on astonished and agog.

Judith hobbled at an incredibly slow speed. We sat down under a tree.

I felt my fever returning to me. (Diary, all of this since my first fever is painful for me to write about!) We continued on the road, only we didn’t go far because Judith’s foot was really bothering her. I took her pack and continued under the hot sun.

I pulled in at the nearest empty roadhouse and sat down. I ignored the prying eyes – by that point I could have cared less, because I sorely needed rest (and Peace!), so I lay down as best I could and read. Judith was “incapable” of going on and it was obvious we’d have to spend the night there. Soon help arrived and we got set up in a shack with a bed. Judith spent her time complaining about the people (who came in hordes). I wished she’d just shut up and be thankful that they were giving us a bed.

I was feverish. I got into the sack long before sundown, and read Hints on Tiger Shooting. I was asked if I wanted tea or milk and said yes, then fell asleep waiting for it. Before dark tea was brought, and I had to drink Judith’s because it had sugar in it − I wish she’d get over her sugar phobia in an effort to simplify these situations and be polite! I think hot milk was brought in the evening. In the middle of the night I awoke with my T-shirt drenched in sweat! I changed into a dry shirt. Judith snuggled up to me and said she had a game plan in her head. She began by suggesting that to convalesce her foot, going ahead to Bharatpur might be the best thing for her to do. I, of course, nodded consent. After all, it made sense. But I had no intention of joining her in a bus ride there. I am on a pilgrimage to my personal God! Of course, I saw it coming (i.e., her plan to divert me from my mission), but I knew not with what force. I suggested the alternative that we could convalesce here in this village. She indicated that for her, that was totally unacceptable. She asked if I’d take the bus with her tomorrow to Bharatpur. I told her, “I’ll wait with you here as long as it takes to convalesce your foot, but I intend to walk all the way to Agra!” She seemed upset when we went to sleep.

Despite all I write negative now about Judith, we still maintain romantic talk and all. Things aren’t really as bad as I write. Through the hardships, if I can maintain a posture of Happy-To-Be-Alive, then despair never gets too close.

Bharatpur – Judith Challenges Me, Accusing Me of Putting My Goals Above Our Love

January 31, 1984

Walking To Bharatpur, India – Didn’t really sleep, so put down this night to walking down the long lonely road to Bharatpur!

In the morning, when I woke, Judith was packing. She gave me a biting lecture on how unloving it was to put my (“stupid”) goals above our love. I told her it would take me more than three days to reach Bharatpur. We went to the road to wait for the bus going to Bharatpur.

People crowded around. I went off to sit on a mound on the other side of the road. I wasn’t happy because our original plan was ruined by her imminent departure. I wanted to get out of there and was hoping her bus would come. Judith came over to me. (Of course, the crowd followed her.) She asked if she’d done anything wrong. I said No. The old lady brought chapatis and supaji from the village. When the people came closer, the old lady handed me a stick to drive them back.

Judith’s bus came. I put her on the bus, much to her resentment. Moments after she left, I put on my pack and began walking briskly toward Mahuwa. I suppose it was about 11:15am. Little did I know I was off on a 24-hour, 50 mile hike! (It was approximately 84 kilometers to Bharatpur.) Some kids followed me, but I quickly shot off the road to walk alone in the fields. I say them spying me from the road. When I’d said goodbye, the kids came close, but the elders chased them away. I said in English, though they couldn’t understand: “No, it’s O.K. (don’t chase them away).” Now, it’s all right. When I’m by myself, it doesn’t bother me.

But later, some boys followed me. I shook my fist at one of them, whereupon they all ran off.

While maybe crazy, I wanted to get to Bharatpur as soon as possible. I wanted to walk 50 miles if I could. I wanted to show Judith that I wasn’t abandoning her and the lengths I would go to be with her. I walked and walked. First the six kilometers to the main road . Then sixteen more into Mahuwa. On the way to Mahuwa, there was another incident. Some guys came past me on their bikes and were aggressively friendly. Later, at a pump-well, they stood by and signaled me to come over. I kept walking. They yelled and yelled. I kept walking. They kept yelling for me to come over to them. They laughed. I threw off my bag and walked up to a boy of my own height. I pushed him. He retaliated. The other boys told me to break it off, so I walked away. But no more than a few steps later, they started laughing. I went for him again. We started sort of wrestling. He had some strength. I had my sunglasses on and didn’t want to break them, so I let go, put my bag on and left.

The rest of the day was uneventful. I arrived in Mahuwa before sundown. I had the most delicious bright oranges imaginable and some fried dahl, chapatis and tea. Thus refreshed, I headed off on the long road to Agra.

February 1, 1984

Bharatpur, India

About 4am or before, I reached a truck stop tea shop. I had tea and even rested for a while. It was another 25 kilometers into Bharatpur. Off again on the road. At Kilometer 20, I lay down and wrapped myself in my tarp and got a little shut-eye after eating the last of my fruit provisions. I was awakened by a strange sound, as if one cat started making a command and suddenly twenty others around all started repeating this horrible crying noise. I realized they were bird calls. With about 12 kilometers to go, I stopped to watch the sunrise. The sun was a big red ball, luminous, awesome.

I thought that for sure Judith spent the night in Bharatpur. But if she didn’t like it she might go, so I wanted to arrive by 10am so that I might find her if she was in the process of leaving. There was a sign: “Bharatpur 7 km.” Mind you, diary, I have been carrying my pack − about thirty pounds, I think, at least − all night. I looked anxiously at every tour bus to see if Judith was on it! I finally got to the park and inside to the Forest Lodge at

10:55am. That was where we said we’d meet. But there was no Judith and no message. So I went over to the Forest Rest House. Again, no message. But finally, one man got the connection of a girl with a hurt foot, and he said she went to the Saras Guest House, just outside the park. I arranged for her to be notified of my arrival. I was dead tired and hungry. I had some coffee and sandwiches at the Forest Lodge, walked to the park entrance, slept on the lawn, then walked slowly to the Saras Guest House. I found Judith’s name in the book. She was staying in the dorm. I was told that she was out in the park till the end of the day. At 2pm, I checked into a double room, had a good hot shower, then went to bed feeling chilled. I fell asleep under the blankets.

About 7pm, Judith knocked. I got up to open the door in the nude, cold, and let her in and ran in the bathroom and then back to bed. I said, “I feel really sick.” And the vibe I got back said: All you think about is yourself.

I started kissing Judith. The mood changed, and some more kissing brought it around to full-on lovemaking. Passionate! Afterward, it seemed evident that Judith and I were both satisfied and happy with the love.

Good day? Bad day? Diary, the trials and tribulations of life must be endured gladly, and I accept them whole-heartedly, as they are directly connected with the many and countless good things, joys and excellent luck I enjoy. However, I really have never liked being ill. It is the one thing about life I don’t like.

February 2, 1984

Bharatpur, India

I slept all morning. I got up because I’d promised I would. Judith and I took a rickshaw into town. I was dying, I was. After a series of stops, we finally made it to the hospital. I had to wait till 5pm to get a blood test. I wanted to lay down. I was given a blanket with dried blood on it. When I questioned them about it, they gave me a clean one. I got my thumb pricked. The doctor proclaimed I had anemia and malaria. He said, “Look how white your hands are!” I replied, “But my hands are always this white!” While Judith saw the doctor, I returned to the guest house by myself. I stopped to eat eggs, curd and chocolate. I went to bed and fell asleep. Judith came in later. In the middle of the night, I vomited all over the bathroom floor, cleaned it up, showered then slept some more.

February 3, 1984

Bharatpur, India

(I note that all the way through the first eight days Judith and I did it − even on the cold asphalt of a road at night under the moon. So, I really must be ill.)

Today, I had no desire to go anywhere, and consequently stayed in bed. It was one of those lost days when there is just a haze and the day passes away. Judith went out to make a phone call to delay her flight and was gone most of the afternoon. I read Hints on Tiger Shooting and slept. When she got back, we talked awhile.

February 4, 1984

Slept at a truck stop near Fatephur Sikri on the main road in a little thatch house, Rajasthan, India

When we woke I certainly didn’t feel like walking, on one hand, and on the other, I wanted to leave this hotel and finish the walk to Taj Mahal because I want to get to Delhi and get proper medical treatment, food and rest. At noon, we checked out and were ready to walk, but Judith had to return her bicycle to town and she delayed us, not returning until 2pm.

We had 55 kilometers to go.We started at about 3pm. 53,… 50,… 45,…, down, down, down went the kilometers. Our spirits were O.K. In fact we got on pretty good. It makes it much easier to walk when you have a good conversation going. By the way, I don’t have malaria – ridiculous! I almost forgot to mention what I do have! Though the hospital said nothing about it, I know I have hepatitis, because yesterday, my piss turned orange and under my eyelids it’s definitely yellow! (I reflect that this whole time I’ve been lugging a 40-pound pack to Agra with a serious illness.) At dark, we kept on. Judith’s foot was doing pretty good.

At 11pm, we pulled into the Fatephur Sikri truck stop to have milk. A guy offered us a bed at the check post across the road to give us a few hours rest.

Arrival at the Taj Mahal – A realization that my personal god is Beauty

February 5, 1984

Agra! The Taj Mahal

In the middle of the night, Judith and I resumed walking. We had about 20 kilometers left to go. The sun rose, the same red ball. We got to a small roadside “town” for breakfast, having milk. On.

We had to start going slow cause Judith’s foot was bugging her. We stopped and started like this every few kilometers. Finally, we got to the outskirts of Agra. We went through a very noisy section of town, crowded, congested. Yuk! We got to the one-kilometer mark and I stopped and waited. Judith and I walked the last kilometer holding hands, and kissed when officially in the city limits. (Which reminds me, Judith’s mouth has got a bacterial infection.)

Judith had to rest her foot, so we pulled into a restaurant. We were told that it was about ten minutes walk from the restaurant to the Taj Mahal! We walked and walked, both broken from sickness and lack of sleep. We finally got to a sign: “Taj Mahal 2 km.”

We estimated it possible to reach the Taj before the sun went down, but just barely… We entered the Taj area. There was a glimpse of a gray-white temple. We said, “That’s it!” In a race against the sun, we went to the entrance. The guard said we had to go around this side and pay two rupees each to get our tickets, but we were in such a hurry I took four rupees and stuffed it in his front jacket pocket. He waved the guard ahead of us to let us in and we entered the Taj grounds.

We sat down with our packs. We got our cameras out and took a few photos, mostly to document our haggard arrival.

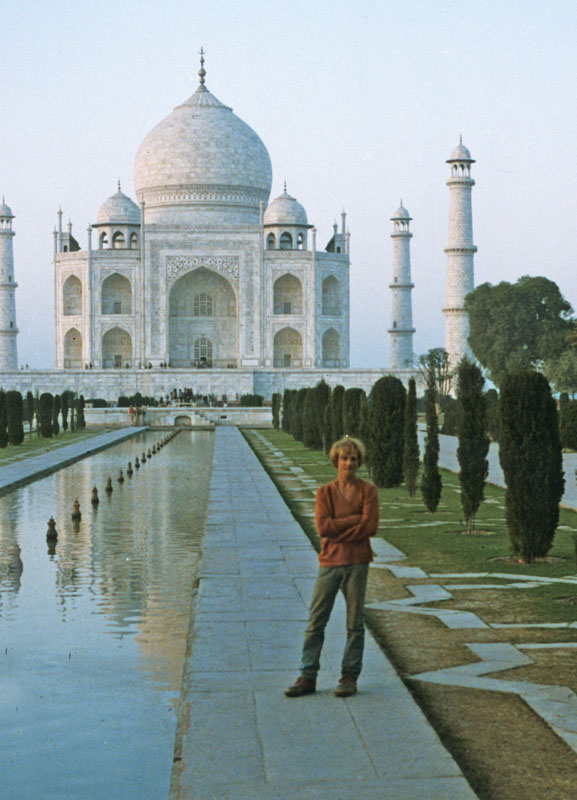

India, Uttar Pradesh Province (State) – 35mm film (Photo by Judith Pollack)

I arrived at the Taj Mahal, sick with hepatitis.

The sky was losing it’s light. Judith went to put her bag away and I walked down the main path leading straight to the Taj, looking, thinking, just seeing. I stopped at the midway point and sat and waited for Judith. We walked to the main entrance of the temple. I stared at it and realized what the god was that I had made a pilgrimage for – it was Beauty… and I realized that my personal god is Beauty.

At the entrance to the tomb, they did not want to let us in with our shoes on, so I took mine off to give them but Judith suggested we walk around the temple first, so we did. I kept thinking “Beauty is my God.” We stopped at the back side. It grew dark.

Behind the Taj Mahal was a thirty-foot drop to a sandy river bed, the river itself being sort of dried up and mucky. Nevertheless, it presented a marvelous scene. There was a crescent moon against the Taj Mahal in the deep pink/violet/black spectrum of the on-setting night sky. I set up my camera and tripod and took a photo.

We were about to leave when we got the idea to go into the temple. We walked around to the front of the building. We rented some tie-on overshoes and went in. We went to where the monument of the graves is on the main floor, where the domed ceiling resounds. (The real tomb is just below this, though at the time, I thought these two sarcophagi held the bodies.) We went in. One of the guards took his flashlight and showed us the inlay on the marble in detail; agate, cornelian, jade, lapis lazuli, onyx, jasper, etc. We used my flashlight and studied the inlay. It was exquisite. The red inlay (cornelian) lit up like a light tube as we held the flashlight against the marble. The marble itself gleamed yellow. I think it was very high quality. Admittedly, I was a little amazed, pretty stoned, in a state of exhaustion, and thus susceptible to suggestion. I was full of emotion. It was such a long walk to get here. I was really feeling it, really getting into it.

Judith went out for a bit. While I was studying the marble, I became overwhelmed by a few feelings. One was that I was overwhelmed by the beauty. I saw my own life in comparison to the beauty there and I felt so terribly lacking. I felt my great spirit and had a heavy heart. I wasn’t really sad. I was just feeling like something hit me. The grandeur around me reminded me of my greater desires and simultaneously reminded me that in terms of the realization of my desires, I was nowhere, nothing. I was so low, and this place so powerful and beautiful. But I welled-over not with grief but with an odd mingling of great, great desire, realism about my present state, awe and respect for the place’s magnificence and a full-of-despair but divinely hopeful desire to somehow lift myself to match the beauty of the Taj Mahal. I broke down in sobs from the deepest well in my bosom and I said to myself: I want to make my life as beautiful as the Taj Mahal! My goal…my desire is to make my life as beautiful as the Taj Mahal!!!!!! I sobbed and sobbed, feeling the emotions I have heretofore described.

Yet a second sort of feeling came over me, and this was an unbridled feeling that spirits of the King and Queen here entombed were aware of my presence. I felt that they were pleased by my fantastic and deep admiration of the monument of their love. I felt that they deemed me special, and I considered that of the millions or hundreds of thousands of visitors who come here each year, I was one of a very, very few that made some great gesture to the temple, as I had walked two hundred miles or so as a conscious prelude to viewing its grandeur.

I also thought that I felt how deeply the King felt grief at the departure of his Queen from this world, the grief that caused him to erect this wonder in her memory. He lay now forevermore beside his Queen. The feelings I had were very warm, and I was filled with emotion over this seeming-communion with the spirits. I was held captivated in the feelings described above for ten minutes or so. When my sobs subsided, I went over to a corner and I lay down on the floor. The temple was empty, at least this small part, though I could hear the guard’s voices from without. Up till now, we’d seen no other tourists up here, only a few workers. I wasn’t sure if the temple was closed or not. (Earlier, when we first arrived to the temple, even before we walked around it, a man had warned us that the temple was closing momentarily.) As I lay there on the cold marble, I looked up. I heard Judith come in. I emitted a ‘godly’ sound, which was not so loud, and I heard it go off into the seeming infinity.

I told Judith about how I had thought we had pleased the spirits entombed here by our pilgrimage. She was easygoing in her acknowledgment of my idea, but maybe she really thought I was being nutty. She might not be wrong about that! Now that we were alone, I got the idea that Judith and I should try to make love. But she said she just didn’t feel right about it.

We decided to go downstairs where the sarcophagi were. There were one or two other parties there. The guard told me how the Taj took 22 years to build, how it was completed in 1653 (330 years ago), and how there was a big diamond once in place on top of the King’s tomb, but it was stolen by some other head of state just eight years after being placed there. He pointed out the symmetry of the place: how the entrance and sarcophagi aligned with the fountains. Very beautiful, truly. I left ten pesa as a donation and apologized for it being so small, but the guard was very nice about it.

Judith and I walked out into the night.