Summit Day on Mount Everest, 1995 – My Journal

Lhakpa Gelu Atop Everest, Summit Cornice With Former Summit Pole, 1995

Tibet, Summit of Mount Everest, taken at approximately 8830m – 35mm film

Seven Summits for a Free Tibet – 1984 to 1997 – Mount Everest (1995)

Background: After nine hours of climbing starting at midnight, my friend, Sherpa Lhakpa Gelu, reaches the summit. I took this photograph of his second ascent of Mount Everest and his first ascent from Tibet. I was standing at about 28,950 feet. Shortly afterwards, Tsering Dorje and I arrived at the summit. The challenge was getting down. The three of us used supplemental oxygen to sleep at the high camp (8200m) and on summit day, but at no other time. But as I climbed, my oxygen bag was often blocked with ice!

If you look closely in the lower left quarter quadrant of the photograph above, you can see the old summit pole. Because the jet stream drops down on the summit, the cornice rolls over, over time. Once you reach the summit plateau from Tibet, it is a gentle walk to the top of the world. Nevertheless, you cannot let your guard down.

Two days after I reached the summit, a climber, Bob Hempstead – “a cowboy from Nebraska living in Alaska” – lost his balance here, slid upside down and backwards and caught his hand on a rock, stopping himself from plummeting 10,000 feet down the North Face. Ang Babu, a Sherpa of amazing physical stamina, and Greg Child, an American who had summited K2, seeing Bob’s predicament, found a shred of old rope, threw it to him and pulled him to safety. Bob, a cowboy intent on doing a rope trick on top of the highest mountain on each continent, went on to summit and performed his rope trick!

What I learned: I could do more than I thought I could do.

Diary entry: On May 24th, 1995 at 9am, I reached the summit of Mount Everest with two Sherpa men, Lhakpa Gelu and Lama (Tsering Dorje). At the time, I could definitely not believe that I had done so, and even now, I can scarcely believe it. It all seems like a dream. In truth, it was the most terrifying 18 hours of my life, 9 hours to ascend and 9 hours to descend. During this time, I really could not believe that I would make it to the summit and/or make it back from the summit. But somehow, with help from my two Sherpa friends, I managed to do both. We left at 12:08am May 24th and returned to high camp at about 6:11pm.

The ascent was not bad, largely due to the fact that it was dark and we traveled by headlamp and, consequently, I could not see the drop off to my right-hand side. Also, as everyone knows, going up is easier than going down. At some point in the expedition, it seems someone, perhaps Jon Tinker (the expedition leader), suggested one might ask themselves the question, “Can I down-climb what I am now up-climbing?” Now, when I asked myself that question, the answer was: “No,” or “Probably not.” One might ask, then, what the devil was I doing up there climbing? It is a good question. Basically, I found myself at high camp with two Sherpas who were expecting me to climb. I was asking myself, “What am I doing here? It is not too late to change my mind…”

We were supposed to begin climbing at 11pm, but I figured that we would be late. Jon had requested by radio that we all sleep in the same tent. I awoke at 10:00pm and was cold, and my oxygen had run out. I went back to sleep until 10:30pm and then, as both Sherpas were still sleeping, I called out.

We left at 12:08am and began traversing upwards towards the ridge. I hadn’t gone 100 steps when Lama pointed out to me that my crampon was coming off: those damn crampons again! I sat down and re-fastened them. The next thing was that we came upon a red bag and some refuse. As Lhakpa Gelu shone his light on it, I noticed that the name tag was from San Francisco. He urged me to forget it and to keep climbing up the mountain, letting out an utterance, though indefinable, which meant “Come on! We have a long way to go.”

Since the Sherpas naturally climb faster than I, they took one of my oxygen bottles, leaving me only one to breathe on. I was silently thankful, for they were moving at a rapid rate, and in order to hike at their natural speed, something had to give. More or less, I was able to do an adequate job of keeping up with them.

Jim from Seattle told me that there was an exposed 40° ice slope at the beginning of the climb. Soon we were on the slope, though it did not seem as bad as I expected. The only thing I was wondering about it was what the exposure would look like if I could see it!!

Next we came to some fixed ropes that went up through some gullies of snow and rock. It was not particularly difficult. But it seemed to go on forever, on up to the right towards the ridge. At a couple of points I thought that I was nearing the ridge, only to find out that it continued on. Because it was dark, I could not make out the ridge clearly. Finally, we started to descend a bit, and I realized that we had reached the actual ridge. Although I knew on one hand the ridge might be harder, still, I was hoping not to have to climb steep ground anymore.

After a while we came to some snow, which we had to traverse. Although the traverse was short, still I hated crossing exposed ground. We came to a level patch of snow onto which fell some fixed ropes. I had to adjust all my things. My pack, my balaclava, I had to take a pee, etc. As Lhakpa Gelu mounted the ropes, he yelled out something. At first I didn’t understand and called out for him to repeat. Then I got it: “The First Step.” Soon I was on the ropes. It wasn’t difficult to jumar and walk up the snow slopes, and soon we were on our way to the Second Step.

The terrain was up and down horizontally on rock. There were ledges that sloped outwardly. Strung along were ropes that were held in place by “pitons,” flat pieces of metal that were wedged into rocks of questionable integrity. The rock was shale and eroding, so whether or not it would hold in a hard fall was of some doubt. But it was dark going up, so therefore conducive to climbing, quite simply because I could not see the exposure. I simply followed the Sherpas as they wound their way slightly upwards and along the ridge, following their head lamps with mine, occasionally stopping to adjust some of my equipment.

The Second Step was visible from some distance, a high ungainly outcropping of rock. Lama and I waited at the bottom while Lhakpa Gelu worked his way up the fixed ropes. He grabbed a whole lot of them (there were between five and seven) and pulled himself over the edge of some rocks. Further up was the vertical section, where, to my surprise was what looked like the Chinese ladder (which I had been told had blown off and was replaced by the new “Japanese” ladder, this being from the recent “Japanese [i.e., 32 Sherpa and 8 Japanese]” first complete ascent of the Northeast ridge this Spring.) I followed. I pulled on the bunch of ropes and hauled myself up, scrambling over the rock edge. It was like scrambling over rocks in the Sierras in California. Then I ambled over to the base of the ladder. It was a solid steel – or, more probably, aluminum – ladder, about 8 feet in height, with about 8 rungs. At the base of it, curled up in a coil, was the “electrical ladder” that the Japanese had used. Apparently, someone had found and reinstalled the famous Chinese ladder.

I switched my jumar over to one of the ropes that led upward from the ladder on the right. There must have been about eight ropes hanging down, all in different stages of wear and fraying. In addition to my jumar, I grabbed the ropes en masse. My crampons rattled against the metal rungs. I ascended to near the top of the ladder. Off to the right above the ladder was a flat ledge. On the ledge, closest to the ladder was a large rock. The problem with ascending it was the transition off the ladder, off and up to the right. It was a bit awkward and it took me a little wrangling to pull myself up onto the ledge. Still the whole process only took maybe five or ten minutes. Once on the ledge, I looked up and over to the right where another cluster of ropes was hanging down. I grabbed them as a group and hauled myself onto the top of the Second Step!

Lhakpa Gelu came over and shook my hand. I also had the feeling of having surpassed a barrier, because in the coming dawn, I could see that from here, it was a gradual walk up the ridge to the summit snow triangle! It suddenly seemed possible that I could actually reach the summit of the mountain! We sat for a bit above the Second Step, changed oxygen bottles, stashed our headlamps by hooking them on to a rope, and generally got ready for dawn and continuing the climb. It was 5:30am.

Lama, Lhakpa and I began to ascend the gradually sloping ridge. The feeling I had was absolutely sensational. The dawn was coming on. The views were unimaginable. The ridge was easy. I looked up at the summit triangle, not far off. I remembered what George had told me. (George Kotov is along as a guide. He is a Russian man, from St. Petersburg.) He’d said that the most difficult part of the climb, he thought, was the Third Step. But beyond that, I wasn’t expecting to have any problems, namely: going up the summit pyramid.

As we walked, I couldn’t resist taking a few pictures. The Sherpas wanted me to continue walking. A couple of times, our path came within a few feet of the east edge of the ridge, marked by a snow drop-off or an arête. I looked down! What I saw was in the realm of the amazing. It was probably 8-10,000 feet of near-vertical relief. Looking over the edge and up, I could see part of the Kangshung Face, the East Face, of Everest.

I thought I saw what was a couple of tents at the base of the “Third Step.” I figured it was the abandoned 8500-meter camp of the Japanese, the “high High Camp” I had heard of. But as we got closer, I more clearly saw that they were merely stashed oxygen bottles, this fact denoting that the distance was much less than I had at first supposed.

The Third Step was surprisingly easy. Perhaps George had not found the same rope we did, as the snow was deeper the day he went up. I watched Lhakpa Gelu go up and followed. The roping was quite clear and good. It wasn’t very far up, and then the walk traversed a small section of arête. Again, the view opened up tremendously on the east side of the arête. It was protected on our side, only requiring to stay to the right of the arête a few feet in order to be safe.

Now we stood on the base of the summit slope. Lhakpa Gelu was already using a red fixed rope to climb the snow. I followed and Lama followed just behind me. The sun was now fully out; it was a glorious day.

Going up the fixed rope was very easy. It was a nice thick rope, newly laid. After the fixed rope, the route traversed up to the right through deep snow for a distance of about 20 meters. This was also easy because the snow was deep and safe. I watched Lhakpa above me. After this section, he went a bit to the right and then up to the left. He seemed to wait for a while and then powered up, kicking his crampons in. At this point, there were rocks straight ahead. He stayed on the snow to the left of the rocks. At the end of the deep snow, I was apprehensive. One option open to me seemed to be to stay in the center of the snow slope, which was slightly bowl-shaped and made of relatively deep snow. This seemed safest to me. While I stood there and contemplated the route I should take, Lama had come up beside me and continued on to the right where the footsteps of others could be seen. I tarried there trying to figure what I should do. I decided to stay in the deeper center of the snow slope. As I started up it, Lama yelled at me to go his way, but I kept on, trying to point out to him that I would soon meet his route. It crossed my mind: until now, I had just followed them and everything had been alright; would I be creating my own problems by deviating from their direction? I kept going upwards slowly, kind of digging my way up, making sure my footing was solid with each step, realizing that this way was a bit more exposed, perhaps, than at first supposed. When I began to rejoin the route Lhakpa had chosen, to my surprise, Lama was going off to the right. He called out for me to follow him. It was perhaps a seemingly inconsequential detail but my position was a couple of feet higher than where Lama stood. This meant that I would have to walk down rather than up, and the exposure at this point in the climb was clearly dangerous.

I stood there looking in two directions simultaneously, up to the left at Lhakpa Gelu and over towards the rocks at Lama. Their instructions weren’t exactly clear, but it seemed they preferred for me to go over to Lama “to the rocks.” They seemed to indicate that it was safer to go to the rocks, but I couldn’t really envision that there was another route so far to the right. I decided to follow the route Lhakpa had taken, up to the left.

I had only covered a few meters when I discovered that I was in an extremely precarious position.

I was clinging to the snow slope, which was about 40° and some of it was kind of icy. At this point if you fall it will take you straight down the mountain and to the Great Couloir and below, probably a ten thousand foot drop. I was very unsure about the footholds and handholds and, given the risk level, I really needed to be as close to 100% sure as possible. I looked up and could see a white rope dangling from the rocks above to the left. I figured if I could get to the rope, I could tie in my jumar to the rope and get the extra support I needed to make upward progress safe, even if I did not put my full weight on it. It was perhaps 20 meters above me. I thought back to Yvon Chouinard’s book, Climbing Ice, in which it seemed he’d stated something like: “When all else fails, chop steps.” So I decided I’d chop steps, even if it took me 1/2 hour to get to the rope. The weather was good and it was only about 8am. So I methodically set about chopping steps up the slope. Mind you this was at an elevation of about 28,750’. Meanwhile, I breathed through my oxygen apparatus at a rate of about 3 liters per minute.

I put in a foothold and then decided to make it deeper or to have a down-sloping aspect to it to make it safer. Then I made another a bit up to the left. Then I swung my ax and tried to get a good purchase as far up in the slope as I could. It sort of bounced off the ice underneath the snow, and I discovered that to the right, there was ice. So I tried to swing a little left in order to try new ground and see if I could get a hold. The ax stuck, but the snow was too soft. Consequently, I tried digging a third and fourth handhold/foothold higher up on the slope for added protection. Then I clunked my ax twice in the spot to the right and got the nub of the ax into the snow, enough to pull myself up given the good footholds I had made. I stood up and took two steps upwards, using the hand hold on the left to further secure my position on the mountain, while my right hand was through the loop in the ax’s wrist loop webbing.

I continued this process methodically, moving slightly left as I moved upward. At one point, I was tempted to rush, but I disciplined myself to go slowly. Soon the rope was only twenty feet away, then fifteen, etc. As I got very close to the rope, I was able to see Lhakpa above me. When I motioned that I was going to use the rope, he seemed to indicate that this was OK. I jumared onto the rope. Once secured into the rope, I realized that I was actually able to move easily up the slope. The problem was not so much one of difficulty with the actual ice climbing, but rather with the fact that it was so exposed. Once on the rope, I found it unnecessary to dig steps, and walked up. Still I used my ice ax as an anchor, and firmly I embedded it as far upwards as I could in order to increase my speed. It was about another 30 meters up and clockwise around the rocks. The rocks at this point seemed no less dangerous to climb since they were quite steep too. Looking up occasionally and seeing Lhakpa, I got the sense that the top was near now. I had gotten through all the summit-bound difficulties and soon would be on top. But I dare not allow myself to think as if it was already accomplished, and I sort of denied to myself that this was so. About five minutes later, I stepped up onto the platform that marked the top of the snow triangle. Off to the left, about 200 meters away, was the summit of Mount Everest!!

Now, reaching it seemed inevitable!

The remaining terrain between me and the summit was easy, although I was just a tad disappointed to see that in fact it was up and down and required some caution as parts of it were somewhat exposed. We three sort of regrouped and then Lhakpa was off again. Just ahead a fifteen-foot section of ground was angled at about 40° and I told myself: this may be easy ground, but do not lose your concentration!!

Not far off, the summit loomed, unbelievably. I told myself that I’d better keep progressing because there was no telling whether the breeze that I was feeling would not grow into a problem. It seemed like it would take about 15 minutes to reach the top. I could see a device on top, which I had heard of. It was some sort of monitor off of which hung multicolored memorabilia; amongst them were prayer flags. Also, I had heard of how a summit pole was stuck in the middle of the cornice which overhung the summit. This pole was once on the summit, but over the years the cornice curled over, pushed by the wind. The pole finally ended up about twenty feet below the summit, stuck sideways in a vertical mass of ice.

Up and down we went, rising gradually upwards. Progress was rapid. Lhakpa was ahead, and Lama almost next to me. As we approached, Lama overtook me and went to the summit ahead of me. Soon, my two companions were standing together on the summit, with me perhaps twenty meters below, gradually plying upwards.

At this moment, it was as if Chomolungma was whispering to me. “_____.” This thought will be with me the rest of my life.

Soon I stood on the top of the world with Lhakpa and Lama. I arrived on top at about 9:11am. At 9:40am, we three departed from the top of the world and carefully made our way down the mountain.

Nine Years later… A tribute to Ang Babu…

August 19, 2004

Richmond, California

Today I met Lhakpa Gelu at the airport at about 10:15pm. We had climbed Mt. Everest together in 1995. Since then, he has climbed Everest a total of 9 more times, 11 in all, and last year, he set a record for the fastest ascent of Everest – from Base Camp on the south side – 10 hours 56 minutes 46 seconds.

View Coming Down from Rocks near Everest Summit, 1995

Tibet, Near Summit Mount Everest, taken at approximately 8800m – 35mm film

After he checked in for his flight, we sat and had drinks – he a Carlsberg and me an apple juice. It was an interesting discussion that covered many points, but mostly climbing and mostly his experiences on Everest. Figuring he was in about the best shape of anyone I could imagine, I asked him some questions about his lifestyle. I will relate the salient points. He drinks about 16 bottles a beer a week and if he exceeds two a day, his wife complains. He sleeps 9-10 hours a day, going to bed at 8pm or 9pm and waking about 6am. He eats just about anything, including sweets. He eats tsampa (barley flour mixed with water to make a dumpling) and ate tsampa, hot water and a few light things on his 18 hour ascent/descent of the South Col route (from Base to summit and back). He does about three expeditions a year, and when he is not on an expedition, he does not run or exercise in any way, but merely stays home and plays with his children. Of note, he said that the North Ridge route that we did was much more difficult than the South Col route. Asked why, he said that it was longer, and when descending tired, you could not just sit on your butt and scoot down, like you could on the South Col route. In addition, he said the Hillary Step was easy, and noted that the Second Step was difficult. He also said that on the North Ridge route, the terrain was more difficult. Inquiring, I mentioned the necessity to step down on small ledges of shale in crampons, and he agreed (that this made it hard). He emphasized that the Hillary Step was easy. I had always imagined it was hard. Lhakpa had climbed the North Ridge 3 times and the South Col route 8 times, so he should know.

I asked about Ang Babu. He was the strongest climber I had ever seen. When asked who was stronger, Lhakpa said Ang Babu was stronger than he. Lhakpa had climbed Everest 11 times with oxygen, but Ang Babu had climbed 10 times without oxygen. (Lhakpa also mentioned another climber, Ang Rita, who had climbed 10 times without oxygen.) Furthermore, Ang Babu had slept on top for 21 hours without oxygen! I told Lhakpa how Ang Babu came strolling up to Camp 3 with a pack that must have weighed 80 pounds. Babu did not seem fazed at all. (Oddly, despite his super-human strength, Ang Babu did not look strong.) I asked how Ang Babu had come to his death. Lhakpa said one evening at Camp 2, after a fresh snowfall, there was a beautiful sunset. Ang Babu went out to take a photograph. Apparently, he could not see a crevasse and slipped into an unseen hole to his death. His teammates noticed he was missing and went out looking for him…

Camp 3 with Yellow Band and Summit Pyramid Above, 1995

Tibet, Mount Everest – 35mm film

From here up we used supplementary oxygen.

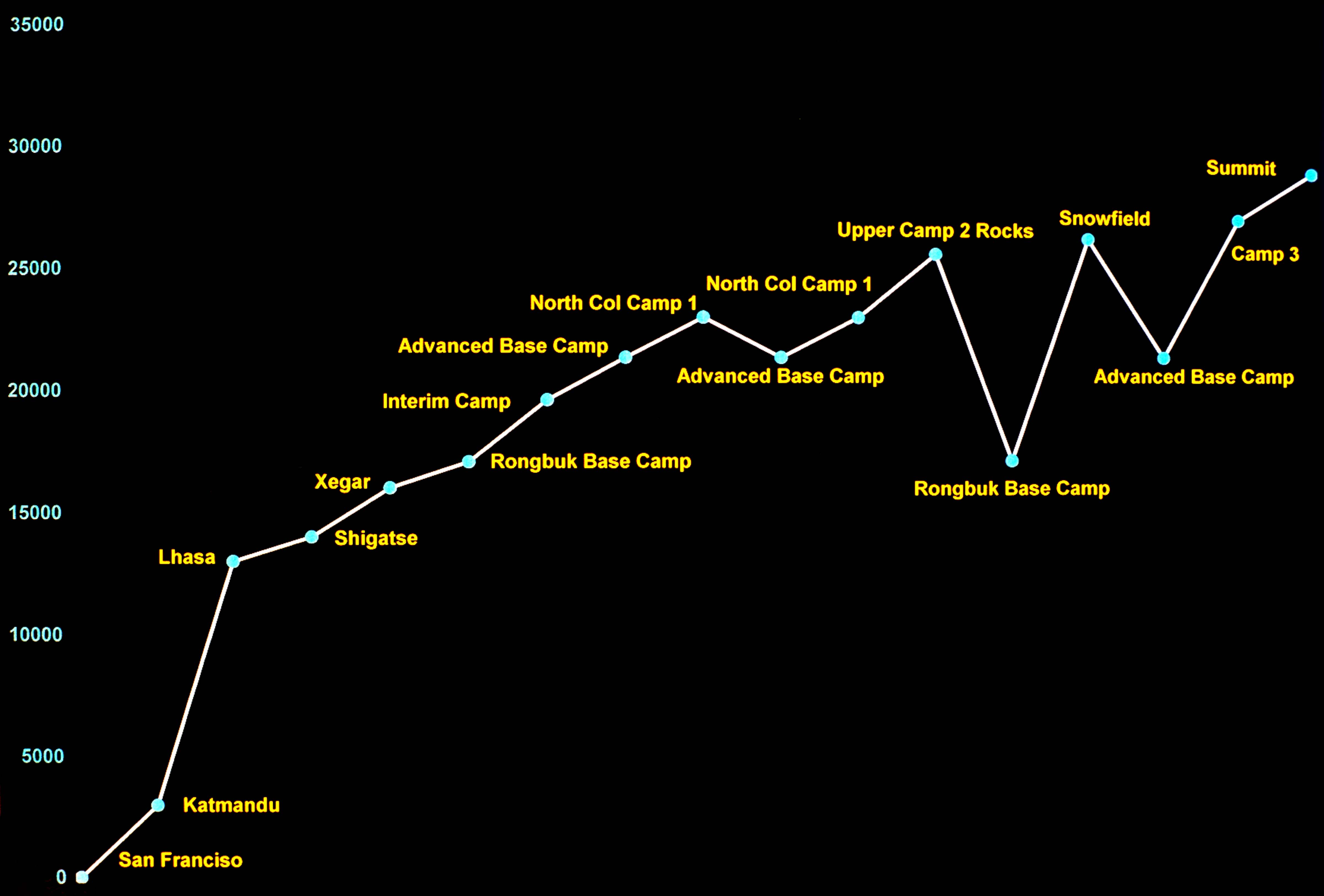

The relative elevations of acclimatization. Advanced Base Camp, 6200m. North Col, 7000m.

Upper Camp 2, 7800m. Camp 3, 8200m. Summit, 8850m.

Tibet, Mount Everest